Emily Tillman, August 15, 2019

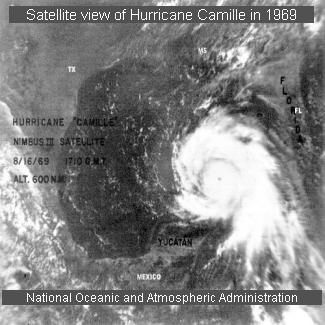

On August 15th, 1969 a Category 2 hurricane struck Cuba. At this point, the hurricane known as Camille hadn’t been anything to write home about. By August 15th when she passed over the western edge of Cuba and entered the Gulf of Mexico, Camille started her trek to making history.

Of course in 1969 we didn’t have the technology we have now to track hurricanes. “We had satellite data, but it was nothing compared to what we have now.” said Chad Entremont, science and operations officer of the National Weather Service in Jackson. ” Still even back then if it was a well developed system you’d probably start to get ship reports and things like that to help out, but we did use satellite information and once we saw something that starts to develop, the hurricane hunters would go out and do investigations.”

Once in the Gulf of Mexico, Camille quickly gained strength to a Category 5 storm. Was this due to the Gulf’s warm waters? “It’s not always just about the warm water. The atmospheric environment really close to it and all around it has to be very supportive for it to develop, and in that case, to get a major hurricane, conditions in the middle and upper part of the atmosphere have to be just right to allow it to develop.” Entremont said.

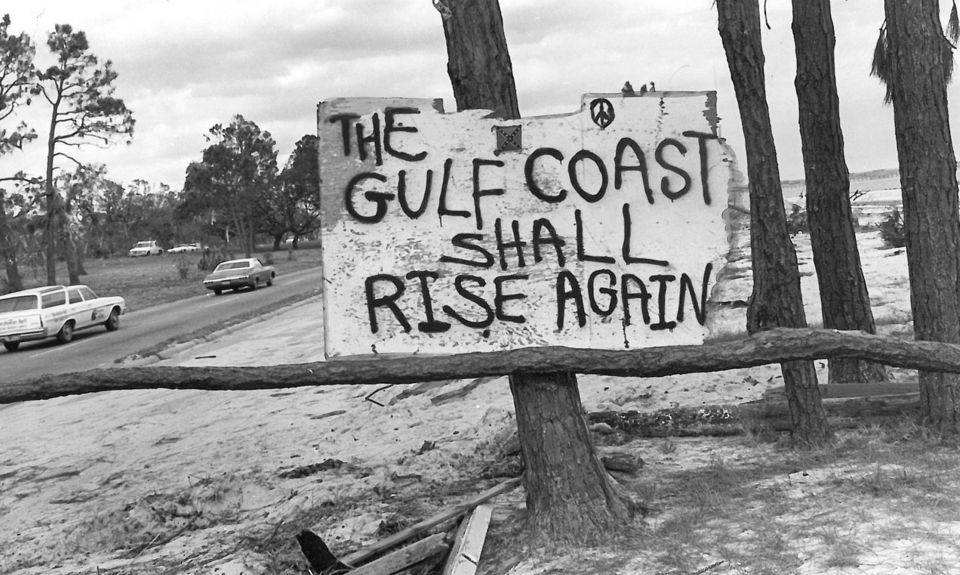

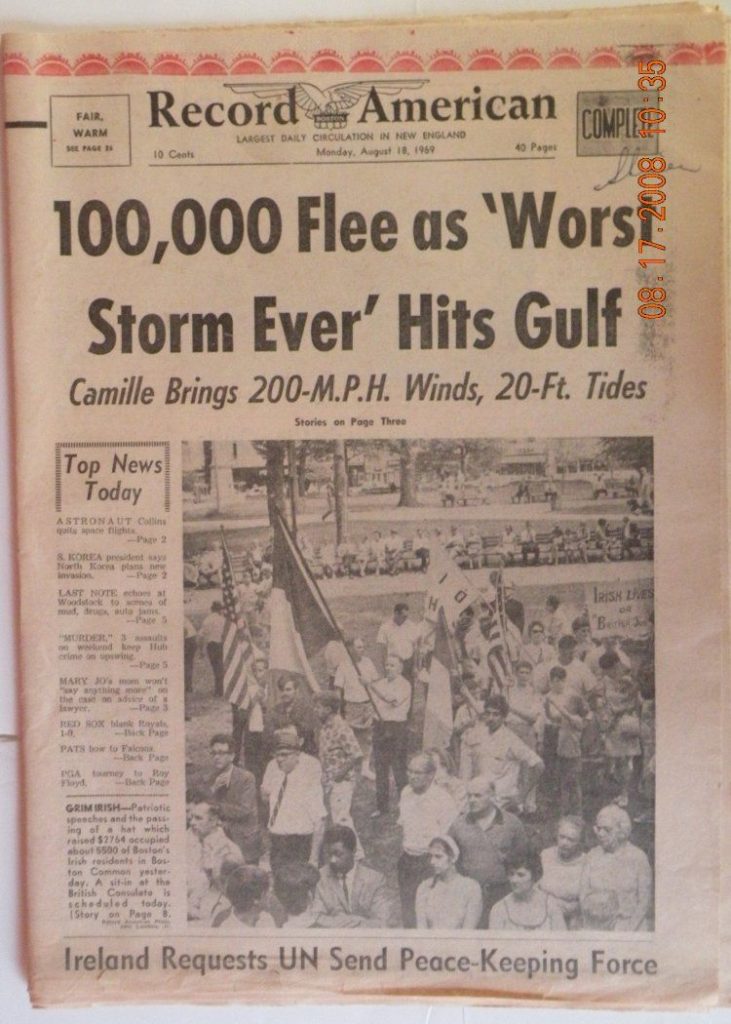

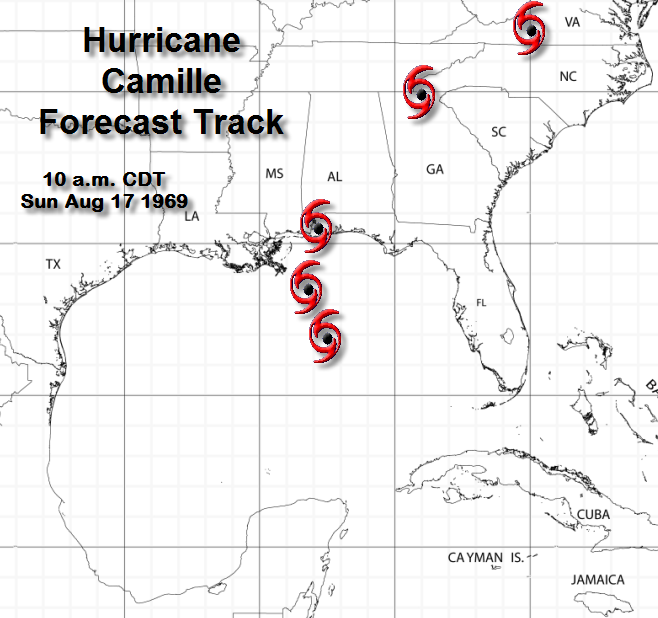

Unfortunately many people did not believe the reports of the storm’s severity and chose to stay on the gulf coast. The mayor of Gulfport ordered the release of prisoners as the storm intensified that evening of August 17th, but none would leave. The storm would kill 143 people along the gulf coast and 153 more in Virginia due to catastrophic flooding. But why didn’t people leave? That’s fairly typical of any hurricane, seemingly especially back then, but there was another factor involved. “I was looking at one of the headlines and one of the advisories that came out. It said Camille and extremely dangerous hurricane that threatens the northwest Florida coast. That headline and that advisory was a day before the landfall.” Entremont said. Did the hurricane change course or was the advisory incorrect? It’s hard to say considering technology wasn’t what it is now.

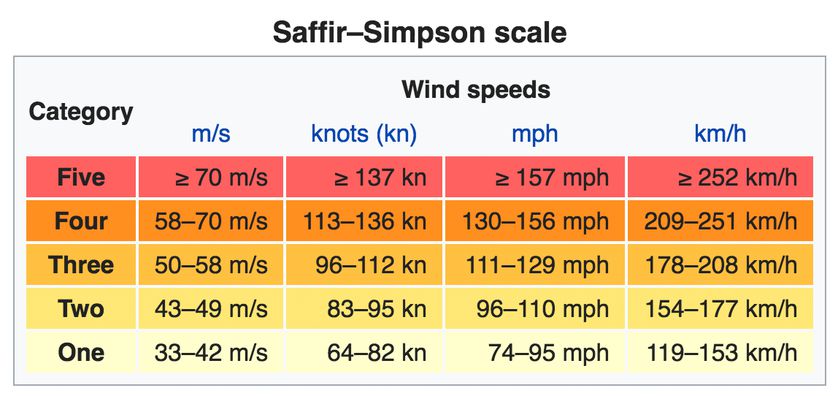

Once Camille made landfall in Pass Christian, MS at 11 pm on August 17th the wind speeds were 172 mph. It is still the most intense hurricane, in terms of wind speeds, to strike Mississippi. In comparison, Hurricane Katrina’s wind speeds were 125 mph by the time it made landfall. It completely decimated the Mississippi Gulf Coast in its wake. The storm surge was 22.6 ft recorded at Pass Christian. “It continued to move north northwest once it made landfall, and it came right over jackson, and it was still a category one when it came through central Mississippi.” according to Entremont. “When it made landfall the pressure was 900 millibars which makes Camille the second most intense hurricane, if you look at just pressure, to make landfall in the United States. ” The most intense in terms of pressure was a 1935 storm that hit the Florida Keys. In 1969, the damages were $1.43 billion which in 2019 is equal to $9.6 billion. Of that $1.43 billion, $950 million was in Mississippi alone.

One thing that came about after Camille was the Saffir Simpson Scale. It was developed in 1971 by a civil engineer named Herbert Saffir and meteorologist Robert Simpson. Simpson was the director of the US National Hurricane Center at that time. Saffir took the idea of the Richter Magnitude Scale used for earthquakes to develop a scale for hurricanes to describe the probable effects of a hurricane.

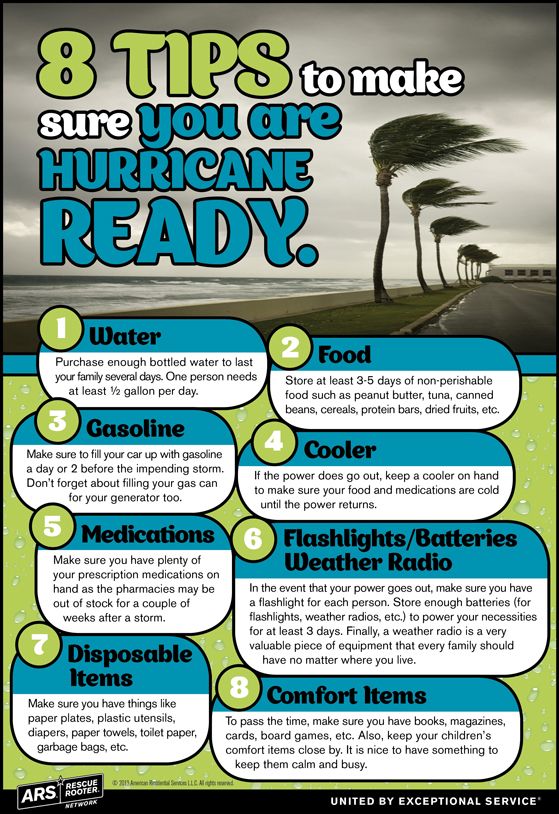

The people at the National Weather Service work hard to make sure we are aware of storms and can take the best steps to be safe. Always adhere to warnings, and it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Vicksburg Radio Everything Vicksburg

Vicksburg Radio Everything Vicksburg